The Falkland Islands

During the Falklands Islands campaign a couple of years ago, much was made in press and radio reports of the inhospitable weather and the bleak, rugged nature of the countryside, but very little was said about local geology. Indeed up-to-date geological information is difficult to obtain from our libraries even in special publications, the reason probably being that such remote territory does not attract much attention apart from exploration for minerals, and reports of this nature tend to remain confidential.

However, odd snippets of information are available from many sources. Charles Darwin visited the Islands twice in “Beagle,” and published his account of their geology in 1846 in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. In 1876 the “Challenger” expedition spent a little time there, and fossils collected at that time were described in 1885, including some fragments of coal found amongst the specimens, from which persistent rumours of mineral wealth have arisen and have never been entirely suppressed. This could even be the root cause of Argentinian interest in the islands, although there is no published evidence that it was anything other than coal washed up from a wrecked steamer.

Several other expeditions made brief reports on Falklands geology over the next forty years, interest being largely in fossils occasionally found which showed that most of the exposed rocks seemed to be of Permo-Carboniferous age, with a striking similarity to rocks of the same age in South Africa and Australia. Ultimately another sample of bituminous or cannel coal with a high oil content, much like that being exported from Australia to Europe, became the justification for a more comprehensive survey, and in December 1920 a qualified geologist, Herbert A Baker, began a project that was to last until April 1922, during which the islands were geologically mapped and accurate information at last became available.

Dr Baker’s report is fascinating. He opens his report by stating that in the first year it rained on 240 days, but that his real difficulties were sudden, violent winds known locally as “woollies” that were particularly menacing when he had to visit cliff exposures along the coasts in an open sailing cutter. He sometimes worked alone on outlying islands, and when he was finished he was recommended to set fire to a patch of “Diddle-dee”, a variety of crowberry everywhere abundant, that would burn fiercely with a lot of smoke. On seeing answering fire from the ‘mainland’, he would go to some shepherd’s house to await the arrival of the cutter, perhaps for a week, before he could be taken off.

In a short article such as this it is impossible to give all of Dr Baker’s findings, but some of his main points are as follows:-

-

The islands owe their existence to local folding of that projecting part of the South American continental shelf now known as the Falklands Plateau.

-

The land is generally low-lying, but with some high relief. A lowering of the land (or rise in sea level) of 25 fathoms would eliminate all the Permo-Carboniferous rocks except the crests of dominant ridges.

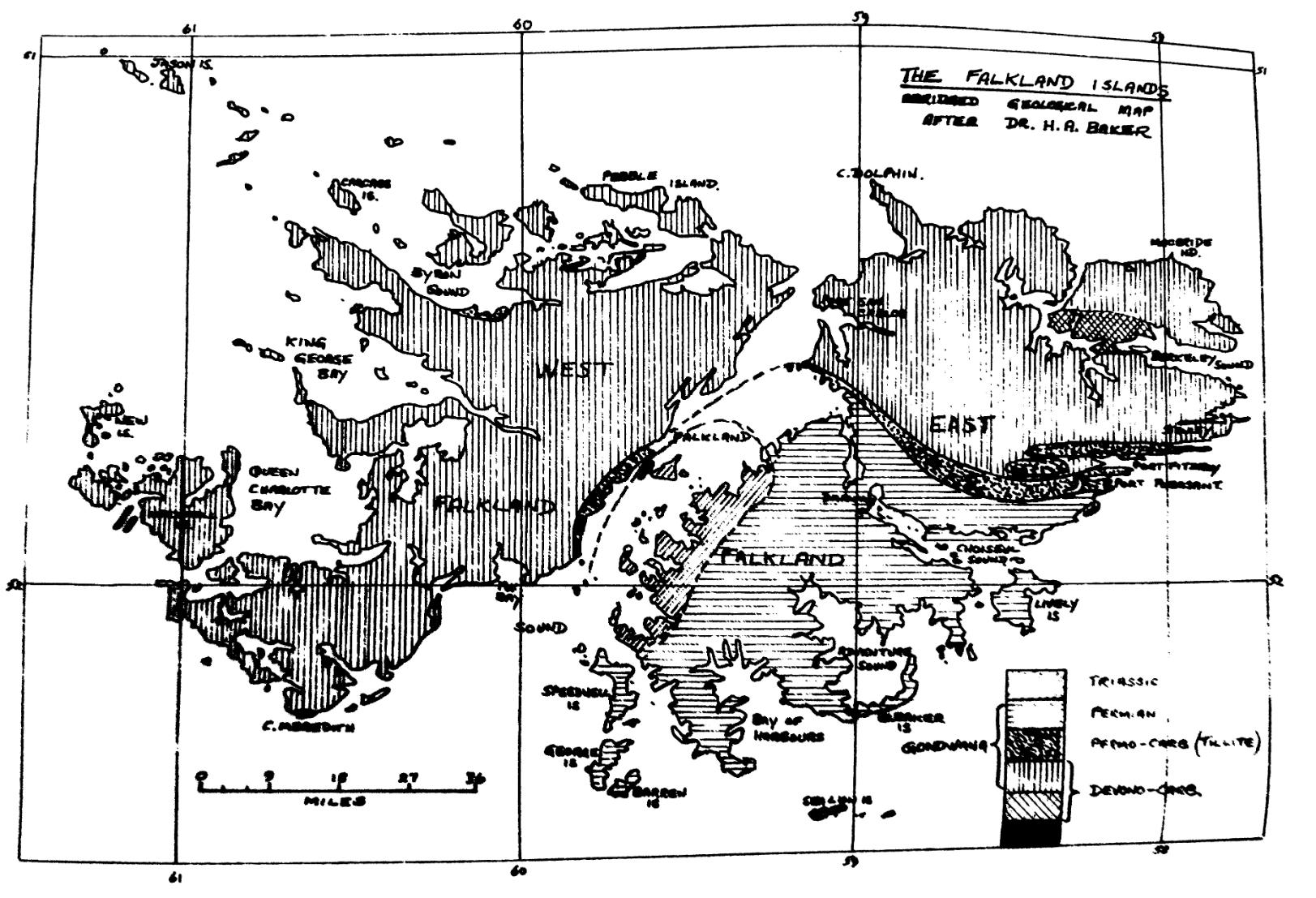

3.The youngest rocks in the islands are Triassic, but rocks of Permo-Carboniferous age are common over a wide area, and the name “Gondwana rocks” was used for them by Dr Baker. There are also large outcrops of Devonian rocks particularly in West Falkland. A small outcrop of Archaean rock was found at Cape Meredith.

-

There are great thicknesses of old Tillite, and more recent “Stone Rivers”, in parts of the islands, showing evidence of glacial conditions, but Dr Baker was concerned about the derivation of these materials in the absence of any higher land anywhere in the vicinity of the Falklands.

-

He found no evidence of any useful minerals in exploitable quantity. There are small patches of iron ore not large enough to be valuable, and there is a pure quartz sand that might well be used for glass-making in a less isolated place. Although brown coal is found in some Australian and S African rocks of only slightly younger age, there was no evidence of anything greater than insignificant traces in the Falklands. Nor was there any surface evidence of oil, although it is found under the continental shelf close to the South American mainland. He advocated deep drilling to prove the point, and suggested places where the exploration might best be carried out, though he was careful to point out that drilling in almost identical rock in the Cape district of South Africa was unproductive.

-

He produced geological maps of the Islands, including tiny islands up to 30 miles from the mainland, and his suggested section from West to East is still considered to be the best available. He also made an excellent and informative collection of fossils from very difficult “collecting country”, which, together with his photomicrographs in which he was a staunch believer in 1920, removed any latent doubts about relationships with S Africa, S America and Australia.

To me, the main fascination in Dr Baker’s report is not in the detail he so laboriously collected, but rather in his recognition that the geology was inexplicable except in the context of the recent speculations of Wegener, known then as his “displacement theory”, but now known to be the beginning of Plate Tectonics, “The recent” the name Gondwana Rocks is of particular interest. His use of the belief that the Falkland Islands were once part of showing his belief called Gondwanaland, though this belief did not a large continent in European and N American universities, him some credibility in was not seriously considered until where continental movement matter the southern universities in the early 1960s. In this America appear to have been more Australia, S Africa and S America disputed his reasons but accepted generous to Wegener in that they disputed his reasons but accepted his principle of Continental movement about 30 years before their northern contemporaries.

For anyone interested in these remote islands I can thoroughly recommend Dr Baker’s geological report, not only as a good read, but also as an example of the heroic enthusiasm of some of our predecessors. Today, with our power boats and helicopters, anywhere land vehicles, and earth-moving machinery, we tend to forget how much excellent geology was accomplished by foot-slogging with a pick, living in wet clothes, and penetrating into inaccessible corners at considerable personal risk.