Field excursion to U.S.A. and Canada, 1984

In June we set off again on our second visit to the great continent of North America, led by that dedicated trio of Bristol University geologists who had bravely planned another marvellous tour for us.

Our trip this time was to be very different from the red rock country of the sunbaked South West which we visited two years ago: this was to be a trip of spectacular mountain scenery, pine forests and lava plateaux.

Our 19 day tour took us on a 3500 mile long journey, amid some of the most stunning scenery imaginable, from the Pacific coast of Vancouver Island to the rain forests of Washington State, the strange volcanic landscape of Craters of the Moon to the snow capped peaks of Canada’s Rocky Mountains. But it was Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming which really held us spellbound, a 3450 square mile wilderness of pine forests, mountain chains, turbulent rivers, steaming geysers and boiling mudpots. Nowhere else in the world is there so rich a concentration of hydrothermal features, which spring to life in many sections of the Park, with dramatic effect upon the landscape.

Yellowstone Lake in the heart of the Park occupies a spot where some 600,000 years ago a giant volcanic explosion occurred, blasting out an estimated 100 cubic miles of Rhyolite lava and ash, and leaving a caldera 40 miles long by 30 miles wide; the largest known caldera in the world.

Although volcanic activity ceased in Yellowstone some 70,000 years ago, there is still a giant chamber of magma within a few miles of the surface, and this is the heat source for the Park’s rich collection of hydrothermal features. Ground water, which is able to percolate deep down through ring fractures surrounding the caldera, becomes superheated, and convection causes it to rise, emerging on the surface at temperatures a degree or two below boiling point. If there are cavities or restrictions in the outflow channel, then a geyser will result, with an intermittent flow since the cavities must fill again after each eruption. If there is a free passage to the surface, a hot spring will result; mudpots form when there is a lot of loose clay and mud material, but very little water to flush it away.

Our first day in Yellowstone was spent concentrating on the main Geyser Basins, where we saw many spectacular geysers erupt, including Old Faithful which spouts water up to 140 feet in the air, and Castle Geyser which has built up a huge cone of the mineral geyserite, formed of silica from the underlying Rhyolite. The hot spring pools came in all shapes, sizes, and an array of stunning colours, from deep blue to turquoise and green, with rainbow coloured surrounds of algae which thrive in the warm edges of the pools and run off channels. Fountain Paint Pots was another fascinating area, filled with seething mudpots, and here it was the sound effects which were so entertaining.

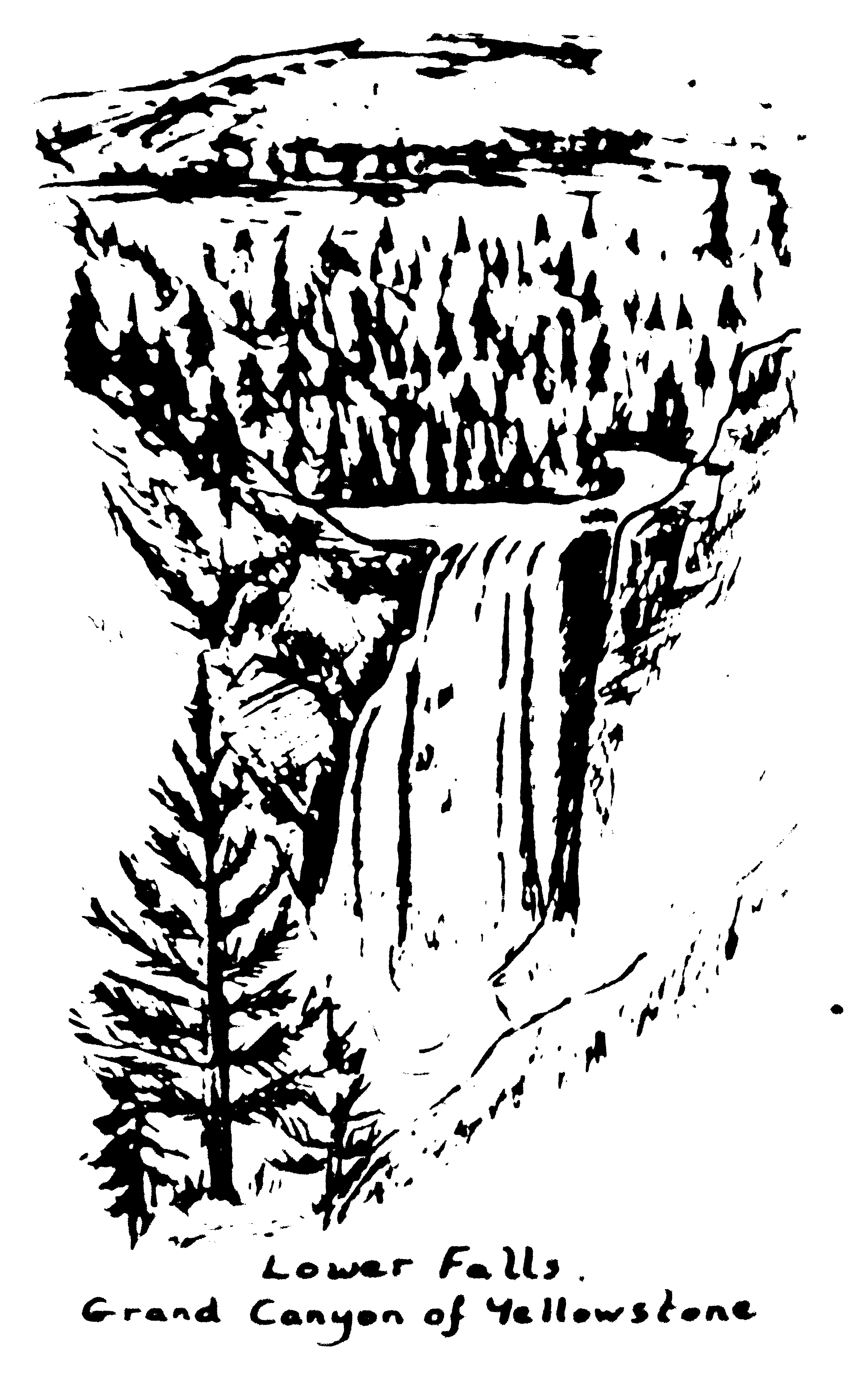

On our second day, we saw some of the Rhyolite lavas and welded tuffs which had been lain down during the formation of the caldera and are now exposed by erosion of the Yellowstone River in the dramatic Grand Canyon of Yellowstone. The rocks, chemically altered by the hot acidic water, are tinged gold and yellow, and it is these vivid colours from which Yellowstone Park derives its name.

On our final day in the Park we travelled north to see the massive basalt columns beside Tower Falls, and spectacular Overhang Cliff which hovered threateningly across the highway. Then as a grand finale, there was a visit to the exquisitely sculptured terraces of Mammoth Hot Springs. These are formed as the hot acidic water readily dissolves underlying layers of limestone and redeposits it on the surface in the form of Travertine. Deposition is rapid - up to one foot per year.

Yellowstone was one highlight of many on our tour. It was a fascinating excursion of geologic wonders and spectacular scenery in the wide open spaces of Western America, truly the trip of a lifetime.