A Recent Temporary Exposure of the Lower Lias (Sinemurian and Charmouthian) Rocks in the City of Bath

Introduction

The outcrop of the Lower Lias in the Avon valley at Bath is generally concealed by 4 metres or more of Pleistocene river gravels and alluvium. Exposures are therefore rare.

In 1978/9, reconstruction of a major sewer to the southwest of the City required the excavation of tunnels and manhole shafts beneath the superficial cover. These excavations traversed the majority of the Lower Lias outcrop from the vicinity of Windsor Bridge Road, Twerton, to Churchill Bridge, near Widcombe. Progress was slow due to wet and unstable conditions underground. Consequently, there was ample opportunity for logging the stratigraphy and palaeontology of the spoil as it emerged from the shafts.

The dark shales, clays and mudstones between the Turneri and Ibex zones yielded numerous fossils, including a series of well preserved pyritised ammonites. These specimens have considerably broadened our knowledge of the palaeontology of this formation in the City. Most of them are now in the care of Bristol City Museum.

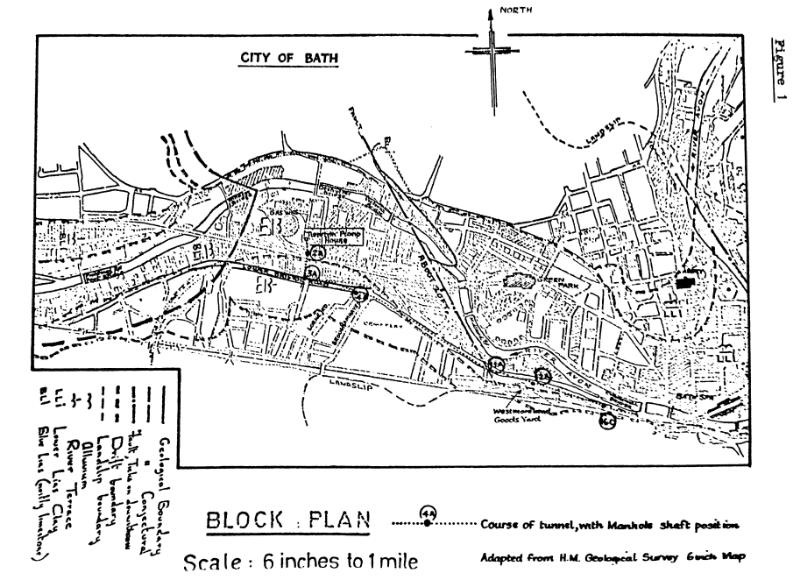

Figure 1 shows the course of the sewer and the principal shafts from which fossils were collected. The shaft numbers are those used by the City Engineer on his contract plans.

Historical background

The limestone and shale sequence of the “Blue Lias” as the base of the formation has been known from scattered exposures throughout the city for two centuries. While the great architects of the Georgian revival stimulated the vogue for Bath Stone (Great Oolite) to achieve their classically inspired compositions, more modest dwellings, and particularly industrial buildings, continued to be built in Lias limestone throughout the Victorian era.

Broadly speaking the limestones reach the sub-drift surface immediately north west of a line between Park Lane, Lower Weston, and Shophouse Road, Twerton. From here westwards, accidents of topography have made them accessible to quarrying, and this is the area where Lias limestone becomes a predominant building material. The old quarries at Newbridge, extending from the river bank behind Hartwell’s car showroom up into Rosslyn Road still show scattered exposures of the formation. Other ancient Lias quarries existed near Gainsborough Gardens, Weston, south of Twerton High Street, and at Pennyquick Bottom.

The other major Lias exposure in Bath, now obliterated, was the Victoria Brickworks pit near Dartmouth Avenue, Twerton. This was still visible in the 1950’s. It evidently endured for nearly a century, since the Charles Moore collection at Bath (approx. 1860) contains bones of mammoth and woolly rhinoceros from the “100 Foot” terrace gravel at this locality. Palmer (1930) indicates that the Lias Clay there, though fairly unfossiliferous, yielded poorly preserved ammonites of the Davoei zone.

The sediments between these two horizons do not appear to have yielded much in the way of accessible material. The collections at Wells Museum include pyritised specimens of Echioceras labelled “Bath”, but their precise source is uncertain. The specimens figured by Walcott (1779) and discussed by Warner (1801), and the species described later by H.G.Woodward (1875) include numerous Hettangian and Lower Sinemurian forms, but nothing which could be attributed to the beds now described.

However, collections in the Bristol City Museum made by Mr. T.R.Fry in the 1920’s from gravel pits at Stidham Farm, Keynsham include specimens of Echioceras and Aegoceras (Androgynoceras) probably derived from the Bath area.

Recent background

Relevant literature and specimens have recently been thoroughly researched by Prof. D.T.Donovan in his preparation of the Bristol District Special Sheet. Memoir (Mem. Br. Geol. Survey). Full details can be found in this work, although it is evident that landslip and superficial deposits have seriously limited the opportunities for study of the Lower Lias Clay. However, the section is especially valuable in this respect.

The Engineering Contract

The total length of tunnel driven was about 2650 metres. The crown of the tunnel was kept below the sub-drift surface to minimise water and collapse problems. Consequently the roof of the tunnel lied generally between 7 and 10 metres below ground level, with the actual distance lessastic sediments.

Prior investigations included a series of 38 boreholes including one at each of the proposed access shafts. These were done between 1965 and 1977 by Geotechnical Engineering Ltd, of Gloucester. The writer has examined all the cores.

Mining proceeded from shaft to shaft, spoil being carted out from consecutive shafts and dumped at Lambridge. The shafts were sunk by the caisson method. Interlocking segments of precast concrete were assembled to form rings 3 metres in diameter, and 600 mm, deep. Shallow circular pits were then excavated, and the rings hydraulically pressed in level with the ground. Further rings were added on top and a further layer of excavation carried out, and successive assemblies forced down until the required depth was reached. The shaft was then capped with a concrete slab and an access lid.

This method of working permitted successive small deposits of spoil to accumulate around the shafts, from which rock sequences could be determined and fossils collected. Matched with the already available borehole cores, the shafts provided an acceptable section through both superficial and solid deposits.

As the major tunnels traversed the outcrop almost in the direction of dip nearly the whole of the Lower Lias became available for study this way.

Figure 1

Geology and Palaeontology

As excavations proceeded eastwards, toward the City centre, consistently younger beds were encountered. The only discontinuity occurred east of Midland Bridge Road, where part of the Obtusum zone seemed to be missing in a shatter belt in where the sediments were hardened, slickensided, and veined with white calcite. The fault responsible for this is shown in Figure 1.

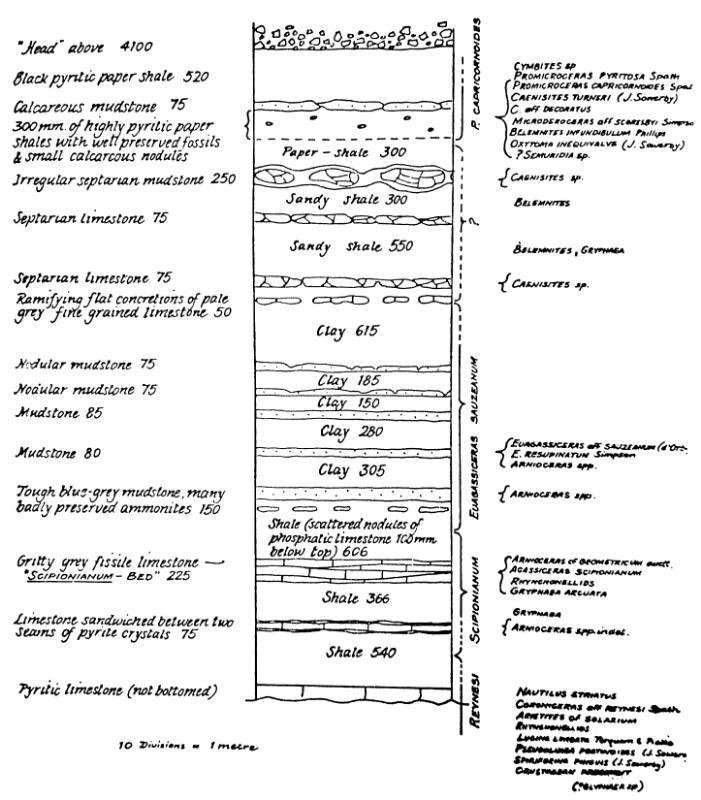

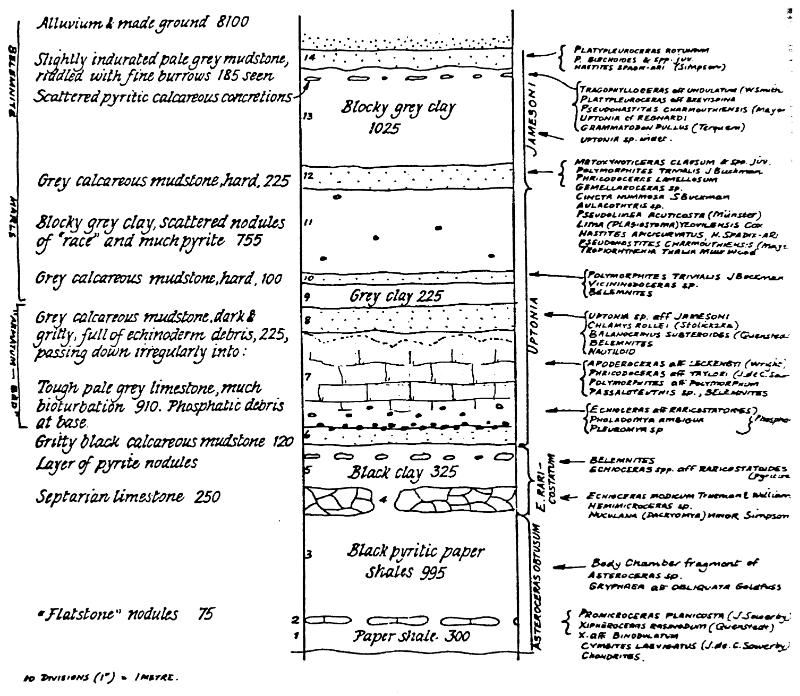

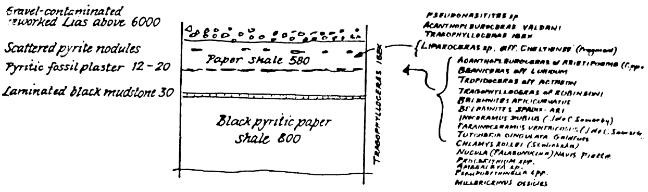

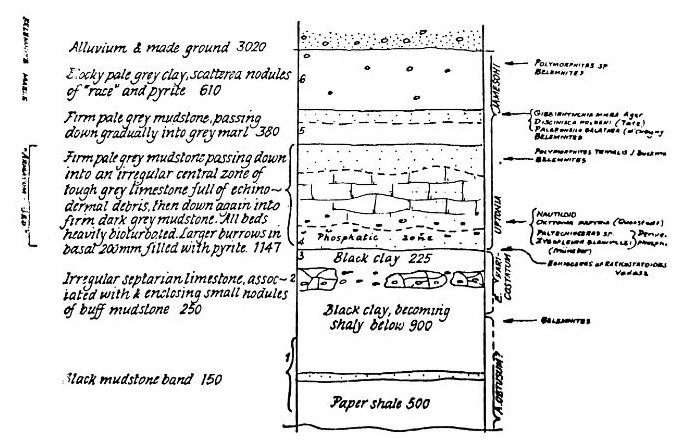

Typical sequences are shown in the attached sections. Figure 2 (Manhole 2A) is typical of the lower or “Blue Lias” part of the succession. This shaft was on the disused railway embankment immediately west of Midland Road. Figure 3 (Manhole 12A) shows the central part of the sequence, two thirds of the way up the Bellamine Marls. This shaft, the deepest on the contract, after 13 metres, was on the approach ramp to Westmoreland Goods Yard. Figure 4 (Manhole 16C) shows the highest beds excavated; clays of the Ibex zone including a pyritic fossil-plaster containing an extraordinary abundance of ammonites. This was sunk on the grassed area outside the administrative offices of Stothert and Pitt Ltd.

Incidentally, higher beds than this (Dyrham Silts, Davoei zone) were recorded by the writer during excavations for the Wells Road/Churchill Bridge traffic circulatory system. So a complete record of the Charmouthian stage exists, taking us back to the rocks once exposed at Victoria Brickworks.

In this necessarily brief account it is difficult to justify the ranking of among points of greatest interest demonstrated by these limited sequences. The most noteworthy one could include:

(a) In the Blue Lias sequence, the intense hardness of the limestone in the limestones and crystalline gypsum (selenite) in the shales. These features cannot be appreciated in the generally old and weathered exposures available today. Also of interest was the discovery of a crustacean carapace (Glyphrea sp.) in the limestone from shaft 2A.

The thickness of these lowest beds agrees with the observations made by Prof. D.T.Donovan in the Keynsham district, (Donovan 1955).

(b) In the Turneri zone, the abundance of pyritised Promicroceras sp. at certain narrowly defined levels. This supports the analysis of ammonite faunas found in the important Stowell Park borehole in 1956.

(c) The apparent absence of the Oxynotum zone. The Elton Farm borehole, Dundry and exposures throughout the Radstock area showed a non sequence at this level, so the absence was not unexpected.

(d) In the Raricostatum zone, the combination of a marine aspect such as is seen in the Black Ven Marls of Dorset, with a phosphatic element recalling the special conditions seen in the sparse condensed deposits of the Radstock district.

The phosphatic debris here is not enclosed in limestone as at Radstock, but occurs in a heavily burrowed hard pyritic mudstone. However, it has the same composition, namely phosphatised nodules, coprolites, bivalves, gastropods and ammonites characteristic of the uppermost subzones of the Raricostatum zone.

(e) The Jamesoni zone shows a typical Belemnite Marl lithology as in Dorset. Once again, however, we are reminded of Radstock on seeing its faunal affinities. There is an ‘item’ [Ammonite] bed at the base containing the typical large tuberculate ammonites (Ampullaceras spp.) and drifts of echinodermal debris all enclosed in a dark mudstone. Higher up come alternating pale grey mudstones and marls containing many slim ‘oxycone’ ammonites of the species Metoxynoticeras and Radstockiceras, as well as early Liopercarates (Vicininoceras). These are typical of Radstock but extremely rare elsewhere, including Dorset.

All the subzones seem to be represented in the Belemnite Marls, which are thin and highly fossiliferous throughout.

(f) Only 2 metres of the Ibex zone were seen, again abundantly fossiliferous. The most remarkable occurrence was a seam of pyrite 12 to 20 mm. thick, consisting entirely of the remains of small ammonites, bivalves, gastropods and belemnites. The ammonites belong to the echinobaldozone of the base of the Ibex zone. The tiny gastropods (Pleurotomaria spp.), pseudobiblites were the same species found to be characteristic of this zone in the Stowell Park borehole.

Although the top beds were cut out east of shaft 16C by the maximum overburden of gravel as the tunnel crossed an abandoned river valley, it is obvious that the Ibex zone, too, must be extremely thin.

Conclusions

These exposures have shed valuable light on the behaviour of the Lower Lias sediments as they thicken northwards, away from the maximum impact of the Mendip Axis.

The Blue Lias, though condensed, maintains the character known from the well-studied exposures around Saltford and Keynsham. The attenuation is not so extreme as in the Radstock district, but neither are the sediments so expanded as they become around Chipping Sodbury and Stroud.

In lithology, the higher beds maintain a vestige of their appearance in Dorset, but their fossils belong to the Radstock faunal province. They do not strictly reflect either Dorset or the Gloucestershire Basin. The sequence is a sort of miniature hybrid between Dorset and Radstock.

Figure 2: Manhole 2a. Location: ST 7381 6437

Figure 3: Manhole 12a. Location: ST 7455 6448

Figure 4: Manhole 16c. Location: ST 7474 6446

Manhole 11a. Location: ST 7440 6450

Figure 5

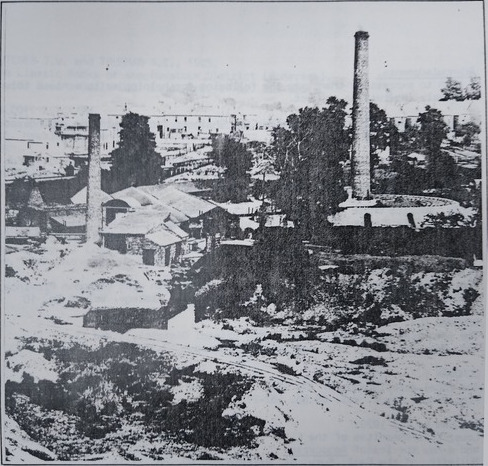

Victoria Brickworks, Twerton, about 1924. The overburden of about 4 metres of Pleistocene gravels (the lighter coloured debris in the foreground) was famous for its content of mammoth, rhinoceros, bison and elk, in addition to abundant derived Jurassic fossils. The sandier fractions were sieved out and mixed with the bricks to reduce shrinkage in times when more suitable sands were scarce - a factor responsible for some very gritty and pebbly batches of bricks produced during the war years.

The Lias clay (some of which can be seen in the weatherings band just forward of the big circular kiln) was full of small pyritic nodules. These often got included in the bricks and their gradual rehydration over the years has led to many of these bricks splitting apart.

The section was not precisely repeated at Churchill Bridge because at this point the terrace gravels overlie the Ibex zone, whereas the Davoei zone outcrops under a mantle of “Head” in the toe of Beechen Cliff higher up.

Acknowledgements

I wish to express my thanks to the following for helping me to achieve this extremely interesting project.

To Delta Construction Ltd. and the City Engineer for allowing me unhindered access to borehole cores and logs, contract plans, and manhole shafts.

To Dr.H.C. Ivimey Cook of the Institute of Geological Sciences, London, for reading the field notes and examining some of the specimens to underwrite the authenticity of the findings.

To Mr. Maurice White (Bristol University Museum) and Dr. M.K.Curtis (Bristol City Museum) for assisting with the identification of the fossils.

References

- DEAN W.T., DONOVAN D.T., and HOWARTH M.K., 1961 . The Liassic ammonite zones and subzones of the north west European Province. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History). Geology, Vol. 4 No. 10

- DONOVAN D.T. 1952. The Ammonites of the Blue Lias of the Bristol District, I and II. Ann. Mag, Nat. Hist. (12), pp. 629-655 and pp. 717-752.

- DONOVAN D.T., 1956. The zonal stratigraphy of the Blue Lias around Keynsham, Somerset. Proc. Geol. Assoc. Vol. 66 pp. 182-212.

- DEAN W.T., DONOVAN D.T., and HOWARTH M.K., 1961 . The Liassic ammonite zones and subzones of the north west European Province. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History). Geology, Vol. 4 No. 10

- DONOVAN D.T. 1952. The Ammonites of the Blue Lias of the Bristol District, I and II. Ann. Mag, Nat. Hist. (12), pp. 629-655 and pp. 717-752.

- DONOVAN D.T., 1956. The zonal stratigraphy of the Blue Lias around Keynsham, Somerset. Proc. Geol. Assoc. Vol. 66 pp. 182-212.

- DONOVAN D. T., 1978. Lower Lias Ammonites of the Elton Farm Borehole and the Dundry Area, Avon, and a new species of Aegoceras. Bulletin of the Geol. Surv. Gt. Britain No. 69, pp. 11-18.

- DONOVAN D.T. and KELLAWAY G.A., 1984. Geology of the Bristol District : the Lower Jurassic Rocks. Mem. Br. Geol. Surv., 69 pp.

- GREEN G.U. and MELVILLE R.V., 1956 The stratigraphy of the Stowell Park Borehole (1949-51). Bulletin of the Geol. Surv. Gt. Britain No. 11. 164 pp.

- HAWKINS A.B., 1966. The Geology of the Keynsham by-Pass. Proc. Bristol Nat. Soc. Vol. 31 pp. 195-202.

- KELLAWAY G.A. and TAYLOR G.H., 1968. The influence of landslipping on the development of the City of Bath. Report No. 23, International Geological Congress, Prague, No. 12 pp. 65-76.

- PALMER L.S., in CROOKALL R. et al. 1930. The Geology of the Bristol District, with some account of the Physiography. British Association for the Advancement of Science, Bristol meeting, 1930.

- TUTCHER J.U. and TRUEMAN A.E., 1925. The Liassic Rocks of the Radstock District (Somerset). Quart. Journ. Geol. Soc. Lond. Vol. 81 pp. 595-666.

- WALCOTT J., 1779. Descriptions and figures of petrifications found in the quarries, gravel pits, etc. near Bath. Bath.

- WARNER, The Rev. R., 1801. The History of Bath. Pp. 394-399, 'Mineralogy and Fossilogy of the Environs of Bath'. R. Cruttwell, Bath.

- WOODWARD H.B., 1876. The Geology of East Somerset and the Bristol Coalfields. Mem. Geol. Surv. Gt. Britain.