The Rhaetian of Hampstead Farm Quarry, Chipping Sodbury - A Preliminary Note

Historical Background

The Rhaetian of Chipping Sodbury was first described by Reynolds and Vaughan (1904) along with a number of other sections that were created when the South Wales Direct railway line was constructed. The Chipping Sodbury cutting exposed a section approximately 650 metres in length showing Rhaetian and Lower lias beds unconformably overlying the old Red Sandstone and Carboniferous Limestone. The site is registered as a site of Special Scientific Interest by the Nature Conservancy Council but is now practically inaccessible and in any case the exposure of Rhaetian beds is totally obscured due to weathering and plant growth.

The next exposure from Chipping Sodbury was that described by Reynolds (1938) in what is now Barnhill Quarry. The Palaeozoic rocks in the area dip to the west at approximately 40°. The quarry lies 1.2 kms north of the railway and therefore exposes part of the same Palaeozoic sequence. Reynolds (1938) described a section of Rhaetian and Lower Lias rocks. Reynolds mentioned the Clifton Down Limestone. These sections are also now overgrown and the only remnants to be found are small patches of basal bone bed adhering to the erosion surface on top of the Carboniferous Limestone.

Following the exhaustion of stone in Barnhill Quarry, quarrying continued 1.4 km further north carrying operations exposing Rhaetian material over encircling dumps of material from surrounding the quarry but there appear to be no records of this phase of the operations. It was not until the driving of a cutting and tunnel eastwards from this quarry for the new Hampstead Farm development in 1974 that Rhaetian beds were again exposed and described by Curtis (1981).

As quarrying progressed southwards in the new Hampstead Farm development, Rhaetian beds were again encountered as overburden and over the last two years as this stripping operation has progressed, numerous sections have been available for measurement and numerous fossils have been collected after carefully allowing natural weathering processes to expose them on exposure surfaces. The work conducted during these two years forms the bulk of the subject matter of this paper.

Description of Sections

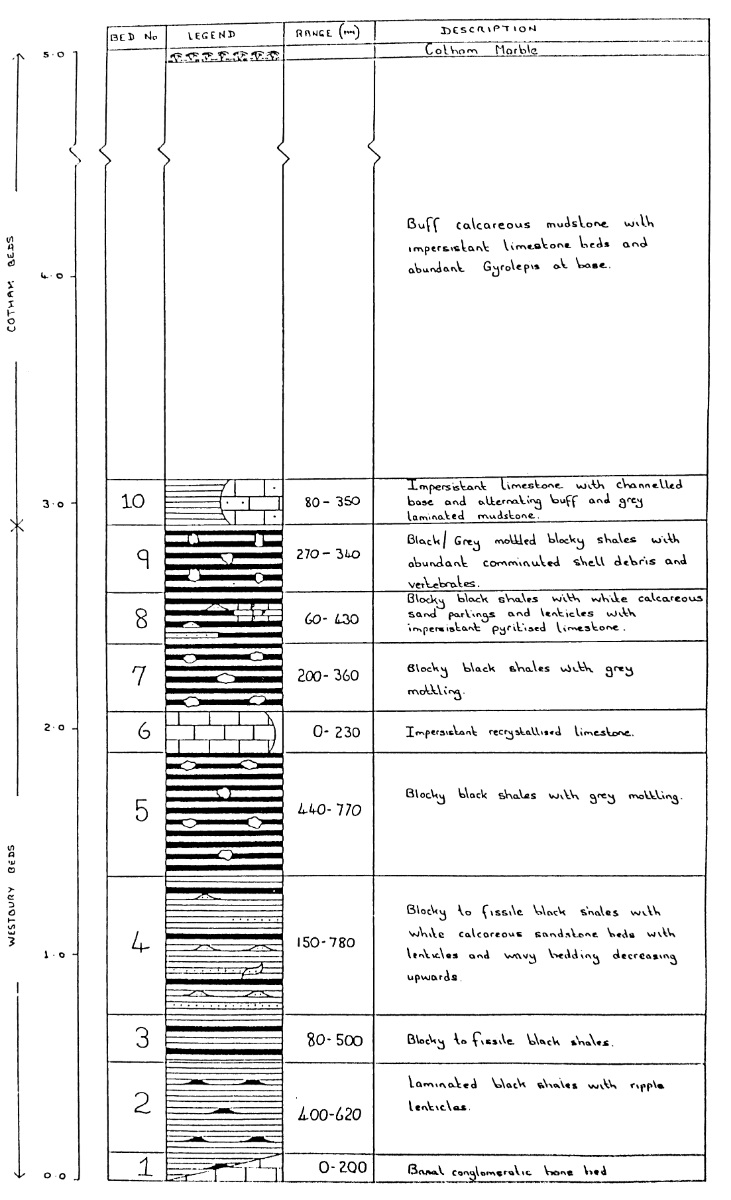

During the process of stripping operations, numerous sections were exposed and a composite section drawn from all of these exposures is shown in Figure 1. It may be noted that this section accords well with those reported by Reynolds and Vaughan (1904) and Reynolds (1938) from the exposures further south.

The basal bone bed is not found overlying either the Black Rock Group or the Gully Oolite but is found above the Clifton Down Mudstone where depressions in the erosion surface formed by different ial erosion of alternating hard and soft beds of fine limestone and calcareous mudstone. The bone bed comprises a conglomerate where grain size seldom exceeds 15mm. It is crowded with disarticulated phosphatised vertebrate remains and the whole is bound by a calcareous cement. The mode of occurrence and fossil content of this bed is identical to that described by Curtis (1981) from Southfields Quarry.

The overlying Westbury Shales comprises a sequence dominated by black shales showing varying degrees of fissility. These shales contain beds with monospecific accumulations of typical Rhaetian bivalves such as Rhaetavicula contorta and Protocardia rhaetica. All of these bivalves are present as decalcified casts. Occasionally thin white beds of calcareous sandstone occur along with sand lenticles and by bedding. This sandstone weathers an ochreous yellow colour. The unimpressioned recrystallised limestone shown in bed 6 is largely unfossiliferous except for occasional Chlamys valoniensis and rarely burrows running along its base.

The topmost bed of the Westbury Shales was characterised by an abundance of vertebrate remains along with ostracods, echinoid spines and calcareous shell debris. The vertebrate remains were not so abundant as to constitute a bone bed but during stripping operations this bed was left in plan exposure for approximately 12 months allowing an area of 16 metres by 70 metres to be carefully searched. This search has yielded a large amount of vertebrate remains. Many were however fragmented due to the use of heavy earth moving machinery for stripping operations. These remains were often discordant with bedding and lay in unstable orientations. For instance, a bone 350mm in length was found lying at about 30° to bedding whilst Ichthyosaur vertebrae were found lying on the lateral surface. The state of preservation of the vertebrate remains is exceptionally good but many had a buff matrix adhering to them which was lighter than the enclosing sediment. Within one exception, all of the vertebrate material in both beds 1 and 9 was totally disarticulated. The exception was the finding of several short lengths of euselachian vertebral column containing up to 4 vertebrae in bed 9.

Apart from the vertebrate occurrences in beds 1 and 9, sporadic scours were found in bed 4. These contained pebbles and reworked pyritised clasts from the basal bone bed.

Vertebrate Remains

Basal bone bed material was subjected to dissolution in 10% acetic acid. These samples were then sieved and their vertebrate content sorted. Samples from the ossiferous bed 9 were also sieved and readied disaggregated in water. This allowed the relative abundance of species to be assessed and these results are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1. Composite Log of Sections in Rhaetian at Hampstead Farm Quarry

| Basal Bone Bed | Bed No 9 |

|---|---|

| ABUNDANT: | ABUNDANT: |

| Lissodus minimus | Gyrolepis alberti |

| Gyrolepis alberti | |

| Birgeria acuminata | |

| COMMON: | COMMON: |

| Hybodus minor | Birgeria acuminata |

| Coprolites | Euselachian vertebrae |

| Osteichthys fin spines | Ichthyosaur sp. |

| Ryssosteus oweni | |

| Coprolites (more containing Gyrolepis) | |

| Osteichthys fin spines | |

| PRESENT: | PRESENT: |

| Ceratodus sp. | Lissodus minimus |

| Saurichthys longidens | Polycardodus cloacinus |

| Sargodon tomicus | ? Palaeospinax fissurae |

| Polycardodus cloacinus | Pseudodalatias barnstonensis |

| Pseudodalatias barnstonensis | ? Myriacanthid |

| Euselachian vertebrae | Saurichthys longidens |

| Ichthyosaur sp. | Sargodon tomicus |

| Plesiosaur sp. | Plesiosaur sp. |

| Ryssosteus oweni | Large indet. bones |

| ABSENT: | ABSENT: |

| Large bones | Ceratodus sp. |

| Hybodus minor |

Table 1. Relative Abundance of Vertebrate Fossils found in Basal Bone Bed and Bed No 9

Most obviously it will be seen that the hybodont shark Hybodus minor and the lungfish Ceratodus are totally lacking in the upper bed. The former of these especially is usually a very significant element of all basal bone bed faunas whilst the latter is usually present. Albeit it is not recorded from a site often simply reflects a low abundance.

Amongst the smaller elements of the fauna, the other two species generally abundant in the basal bone bed are the shark Lissodus minimus formerly Acrodus minimus but now redescribed by Duffin (1986) and the fish Birgeria acuminata. Whilst the latter is still fairly common, Lissodus which is usually the commonest element in basal bone beds is reduced to a minor component of the upper bed.

The abundance of euselachian vertebrae is of great significance. The euselachian or ‘modern level’ sharks are a group comprising the living sharks and their fossil relatives. The oldest known example is Palaeospinax recently reported by Duffin (1982) from the basal bone bed of Aust Cliff. Vertebral calcification is taken to be diagnostic of the euselachian sharks (Reif, 1977). Whilst these vertebrae are generally quite rare in the basal bone bed, they are very common in bed 9 with more than 700 having been collected to date.

Amongst the shark fauna of bed 9, not found in the basal bone bed are teeth of the Polycardodus hollwenlensis, Palaeospinax fissurae and a myriacanthid. These identifications are however unconfirmed, the first two species having been identified by C.J. Duffin from Somerset but not yet described (Duffin, pers. Comm.).

Ichthyosarian remains are more prominent in the upper bed. Remains identified include teeth, fragments of jaw bone, vertebrae, paddle bones, a femur and rib fragments. There would also appear to be two species represented on the basis of size comparison of paddle bones. The larger is represented by a paddle bone of 15mm in diameter whilst the rest of the bones are comparable in size to those of the lower Lias Ichthyosaurus Leptoptyngius tenuirostris. Plesiosaurs are represented only by teeth and vertebrae.

The invertebrate remains may again be divided into two groups with significant finds in the smaller, the relatively rare Ryssosteus oweni, is represented by numerous vertebrae and bone spines. A number of small limb bones, most fragmentary, are referable to this species. Apart from these smaller bones, a number of fragmentary, larger bones have been found which are not determinable. The largest of these was 500mm in length and 60mm wide.

Invertebrate Remains

Apart from the invertebrate remains discussed above, bed 9 contains several types unique to the section. The first of these is an abundance of ostracods which have not yet been identified.

Echinoid spines have also been retrieved from the sieved residues. The only previous records of echinoids from the British Rhaetian are of opiuroids and one occurrence of regular echinoid spines from beds belonging to the Cotham Member (Duffin, 1980).

Ammonites are totally unknown from the British Rhaetian despite being present in the Tethyan realm where they are used as zonal fossils for the whole of the Triassic. One very small (3.6mm in diameter) example has been found in bed 9. This ammonite shows simple goniatitic sutures and could be the first recorded ammonite from the British Rhaetian. It is possible that this fossil could have been reworked from earlier deposits. This is however considered to be most unlikely because this bed is notable for its extremely low content of derived fossils. Only one certain example of a derived Carboniferous crinoid ossicle has been found.

Discussion

The section recorded here accords well with those previously published from the south around Chipping Sodbury (Reynolds and Vaughan, 1904 and Reynolds, 1938). The most significant feature is the presence of the ossiferous bed 9. Reynolds (1938) recorded a limited fauna in the region of this bed from Barnhill Quarry.

The vertebrates in bed 9 range in size from less than 1mm to 500mm and are contained in a mudstone matrix and their orientations are not of a stable type. Furthermore, they are all disarticulated and many have patches of matrix sticking to them which is of a lighter colour than the enclosing sediment. It would be impossible for bones to be deposited in this fashion under the lower energy conditions normally associated with black shale deposition. It is therefore suggested that this bed represents a storm event where deposition normally occurred between normal and storm wave base. Onset of a storm then caused the sediments to be picked up and churned by wave action until the passing of the storm allowed the sediment to drop with enclosed vertebrate remains settling in a chaotic fashion. The presence of some fossils with a ‘foreign’ matrix suggests that the material was brought into the basin of deposition from outside. Transport however must have been minimal because most of the vertebrate remains show little or no abrasion.

The changes in vertebrate fauna between the basal bone bed and bed 9 show a marked decrease in the abundance of hybodont sharks and an increase in abundance of euselachian sharks and Ichthyosaurs. Amongst the osteichthys, Gyrolepis becomes more abundant. In spite of assertions in the literature to the contrary (see for instance Savage and Large, 1966) these findings at Chipping Sodbury confirm a similar faunal change reported by Duffin (1980) from the Chilcompton section, Somerset. Whilst Duffin expressed reservations about this change, the confirmation of an identical change in piscine abundance between two widely separated geographical localities suggests that this feature should be investigated more fully throughout the British Rhaetian.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our thanks to Mr. N.J. Eastwood, Manager of A.R.C. Chipping Sodbury Quarry for his helpful co-operation and permission to repeatedly visit the site.

References

- Curtis, M.T. 1981. The Rhaetic-Carboniferous Unconformity at Southfields Quarry, Chipping Sodbury, Avon. Proc. Brist. Nat. Soc., Vol. 40, pp. 31-35.

- Duffin, C.J. 1980. The Upper Triassic Section at Chilcompton Somerset, with notes on the Rhaetic of the Mendips in General. Mercian Geol., Vol. 7, pp. 251-268.

- Duffin, C.J. 1982. A Palaeospinacid Shark from the Upper Triassic of South-West England. Zool. J. Linn. Soc., Vol. 7, pp. 1-7.

- Duffin, C.J. 1986. Revision of the Hybodont Selachian Genus Lissodus, Brough (1935). Palaeontographica, Vol. 188, pp. 105-152.

- Reif, W.E. 1977. Tooth Enameloid as a Taxonomic Criteria: 1. A New Euselachian Shark from the Rhaetic-Liassic boundary. N. Jb Geol. Paläont. Mh., 1977, pp. 565-576.

- Reynolds, S.H. 1938. A Section of Rhaetic and Associated Strata at Chipping Sodbury, Gloucestershire. Q.J. Geol. Soc. Lond., Vol. 75, pp. 97-102.

- Reynolds, S.H. and Vaughan, A. 1904. The Rhaetic Direct Line. Q.J. Geol. Soc. Lond., Vol. 60, pp. 194-212.

- Savage, R.J.G. and Large, N.F. 1966. On Birgeria acuminata and the Absence of Labyrinthodonts from the Rhaetic. Palaeontology, Vol.9, pp. 135-141.